What begins as a lighthearted – albeit stressful – birthday celebration for a friend quickly devolves into chaos as a group of gay men in the late 1960’s confront their deepest fears and regrets in this haunting, yet hopeful adaptation of the hit play The Boys In The Band. It is specifically an adaptation of the recent Broadway revival, with the main cast returning for a stellar Ryan Murphy and Joe Mantello production that is benefited by being nothing like any of Murphy’s other recent projects: his flair for the overproduced and melodramatic grows tired after a while, which is why the stark simplicity of The Boys In The Band‘s single set (with a handful of other locations, such as city streets and rooms glimpsed through hazy, brief flashbacks) and small, close-knit cast is so wildly refreshing – Mantello, who directed both the revival and this film, brings the essence of the play to life onscreen with tricks learned from a long theatrical career, without needing to fall back on Murphy’s typical tools; a kaleidoscope of colorful costumes, eccentric set design, juicy yet nonessential plot filler, etc. Instead, The Boys In The Band strips everything back, peeling away layers just as harshly and honestly as lead character Michael (Jim Parsons) does to his unsuspecting friend group.

The Boys In The Band was written during – and takes place in – a very uncomfortable period of the LGBTQ+ community’s history, in the year or so before the infamous Stonewall riots, and that information is intensely important for anyone who plans on watching or reviewing the film, in my opinion. When it was first released, the play was supposed to be a stinging, cynical depiction of the pain within the gay community; pain that, at the time, was often internalized, resulting in feelings of self-loathing…but in retrospect, I believe it can now be looked at as an expression of how that pain and anger grew within the community until it could no longer be contained, and was instead channeled into the creation of the Gay Liberation Movement after the events at Stonewall – a movement that tried to undo decades of emotional damage, by emphasizing self-pride and celebration of one’s sexuality. Thus, while the original play struck a bitter tone and ended on a note of abject hopelessness, the film doesn’t quite do that. Although it shines a harsh spotlight on pain and hatred and the way in which a straight-passing lifestyle was (and occasionally, still is) often held up within the community as an ideal even at the expense of personal happiness or comfort, it also cleverly finds ways to depict how the gay community was growing slowly stronger, self-reliant and independent at the same time. Even though the characters in The Boys In The Band can’t see or even begin to imagine the monumental changes happening all around them, the audience can understand that the feelings of connection, loyalty and trust they develop over the course of that one night in Michael’s apartment are the same feelings that would go on to empower the LGBTQ+ community in positive ways. Particularly connection with others, which, while healthy no matter who you are, or what your sexual orientation is, has always been especially valued in the LGBTQ+ community because of how critical it was during the early days of the movement. In just a couple of added scenes near the end of the film, Mantello gets this point across perfectly.

It is also, in my opinion, a far more genuine method of weaving hope into a bleak narrative than Ryan Murphy accomplished with his recent series Hollywood, which made the bold decision to just completely rewrite the entertainment industry’s history, giving fairytale endings to a mostly imaginary cast of characters and steamrolling over the real trailblazers who fought to make change and progress happen.

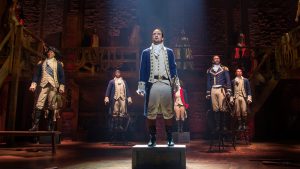

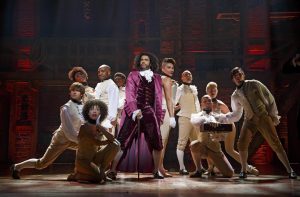

Aside from its cultural significance, The Boys In The Band is worth watching for its outstanding cast alone – an all-LGBTQ+ cast, I might add. There’s still a fervent debate over whether or not only gay actors should play gay roles, but no one can convince me that it’s not exciting and inspiring to see so many openly gay actors bringing their all to these roles and having a great deal of fun in the process (and yes, this movie is a great deal of fun: not only is the element of suspense entertaining – up until it’s intentionally not – but the humor is witty and playful throughout the first act).

Jim Parsons, fresh off Murphy’s Hollywood, is back again playing another cold-hearted yet strangely hypnotic force of nature: his Michael is a fearsome, anxiety-ridden character who eases his own pain by passing it on to others during the infamous telephone game he proposes about an hour into the film – the rules are simple: call the one person you believe yourself to have truly loved, and tell them you love them, and you win points for how well you do and how many of Michael’s criteria you meet. The results, on the other hand, are anything but simple, as characters go into the game energetic and optimistic, only to end up feeling betrayed, ashamed and wracked by guilt. And as for Michael, he seems to feed off these feelings, all while he eagerly tries to guide the game back around to the one person whose opinion he actually cares about: his seemingly straight friend from college, Alan (Brian Hutchison), who has come into the city for unknown business and whom Michael is convinced is secretly gay. Jim Parsons fills the character of Michael up to the brim with emotion that threatens to spill over at any moment, as he initially attempts to sterilize the mood of the party in an attempt not to offend the fragile Alan, only to then do a heel-turn and actively try to force Alan to out himself.

Zachary Quinto excels in the coveted, enigmatic role of Harold, giving his character a slinky gait and commanding presence; though, for all his outward confidence, he too is wounded within. Robin de Jésus is a pure bundle of joy as the proud, unabashed Emory, probably the only character who seems happy because he is happy – and who is thus subjected to the most verbal and physical abuse throughout the film. Michael Benjamin Washington’s Bernard is quiet, understated, and has one of the best scenes in the entire film as he is the first to participate in Michael’s telephone game and the first to suffer the consequences – a reflection of how Black people and people of color in the LGBTQ+ community have always suffered discrimination both from without and within the community, despite historically always being at the forefront of the movement for LGBTQ+ liberation. The only actor I never felt strongly about one way or the other was Matt Bomer as Donald – his character is important to the story, but Bomer doesn’t really have a chance to do all that much with him.

Credit has to be given to everyone who designed, decorated and lit Michael’s charming, two-story apartment. The entire set is vivid and clearly lived-in, as it has to be since we spend almost the entire film in this one small space, exploring virtually every nook and cranny from the bathroom to the kitchen to the inviting terrace decorated with balloons and string-lights – never once does it feel cramped or enclosing. And never once does it feel like Ryan Murphy stepped in and demanded anything had to be bigger, or flashier, or more lavish: Joe Mantello, who worked with an abstract set for his The Boys In The Band Broadway revival, has brought an effectively simplistic sensibility to the production design for this film that nonetheless comes off as organic and appropriate rather than a gimmick meant to turn the film into an imitation of the theater experience.

What is there left to say? Only that, with The Boys In The Band, Murphy and Mantello have crafted something hilarious, haunting and hopeful: a poignant restoration of a story that has immense significance to the LGBTQ+ community. While the play presents a contemporaneous account of a group of men suffering trauma embedded deep in American gay culture, the film has the benefit of being able to assure us that, even though not everything would be solved with the Stonewall riots or the creation of the Gay Rights movement or the legalization of same-sex marriage or any of a hundred other landmarks, the world would begin to change, both for the characters in the story – and for us, the audience, who find ourselves in another dark time, where human rights (including those which the LGBTQ+ community have fought for and won) are being threatened and actively removed by the current Presidential administration. At this moment, The Boys In The Band is just as necessary and relevant as it was back in 1968, as a reminder that your anger at injustice is your greatest weapon against divisive forces, and that, even when the whole world is trying to get you to direct that anger inwards at yourself, you have the power and the right to use it for good.

Movie Rating: 9.5/10